| Between

the Jerusalem Plank Road battle and the end of July the

Petersburg-Richmond front was quiet. Jubal Early's

success in the Shenandoah had been translated into an

invasion of Maryland and an attack on the suburbs of

Washington, which had forced Grant to detach VI Corps to

defend the capital and also to send XIX Corps, recently

arrived from the Gulf area. (It is one of the more

interesting "what-ifs" to consider the impact

of Grant keeping VI Corps and adding XIX Corps to the

Federal forces operating around the Confederate capital

that summer.) Towards the end of July Grant decided to launch what would be the first in a series of "double-enders," attacks that would first lunge at the Richmond flank and then later threaten the Petersburg flank. The motivation for the July operation was complex. It partly was due to the failure of the divided Federal command in Washington to defeat Early's force, and it was partly due to the development of Burnside's mine. The story of the mine is fairly well-known. As early as June 25, men in the 48th Pennsylvania (1/2/IX) had suggested digging a mine under the Confederate earthwork opposite their position, and the project had been enthusiastically endorsed all the way up to corps level (Burnside). The Army of Potomac staff was less enthusiastic, largely due to personal and professional jealousies. As a result the construction was accomplished in spite of, rather than because of, the efforts of the Army of Potomac staff, and the lion's share of the credit should go to Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants of the 48th Pennsylvania. When the mine was nearing completion it began to dawn on folks that, since the thing had been dug, it might be a good idea to develop a tactical operation to exploit it. Grant decided to combine the mine attack with an operation north of the James and ended up devising perhaps the best-conceived operation of the entire siege. |

|

||||||||||

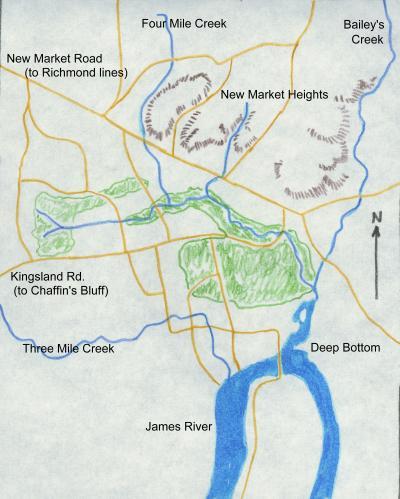

First Deep Bottom (July 26-29) On the evening of June 19, only a day after the failure of the initial attempts to carry Petersburg by storm, Grant ordered Butler to send a brigade of not less than 2,000 men to "seize, hold, and fortify the most commanding and defensible ground that can be found" on the north side of the James River. This was to establish a bridgehead that could be defended, perhaps with the aid of gunboats in the James River, and from which future operations might be launched against the Confederate capital of Richmond. The task was carried out on the night of June 20th by Brig. Gen. Robert S. Foster, commanding 3/X. Foster's position was on the west side of Bailey's Creek, which flowed south into the James River at a place known as Deep Bottom. The existence of such a bridgehead was of course a threat to Lee's position, but the Confederates did not have the force available to drive Foster back. On July 6th Lee asked Ewell, then in command of the Department of Richmond, if he might not be able to drive the enemy away and destroy the bridge, but no serious effort was apparently made at that time. However, the Confederates were able to harass Federal shipping on the James with artillery. In response to this, Grant ordered a second brigade into the bridgehead, in order to occupy more ground and prevent the harassing artillery fire. This was done on July 23rd, and resulted in the expansion of the Federal foothold to the east side of Bailey's Creek. The presence of a second brigade north of the James was enough to provoke a Confederate reaction. Lee ordered Kershaw's division to move from its position at Petersburg to the north side of the James, to drive off the two Federal brigades. Kershaw moved out promptly and launched his attack on the morning of July 25, driving back the newly arrived Yankees east of the creek. Federal counterattacks were unable to retake the position, so Grant ordered reinforcements sent. Typically, Grant did not simply respond to the Confederate moves; rather, he took the occasion as an opportunity for an offensive of his own. On July 25, Grant outlined his plans in two notes to Meade. Hancock's II Corps, together with two divisions of cavalry under Sheridan plus Kautz's division of cavalry from the Army of the James, would cross to the north side of the James at Deep Bottom, drive off the Rebels threatening the bridgehead, and advance on Richmond. If carried out expeditiously, the operation might actually result in the fall of Richmond, but Grant acknowledged that this was unlikely. The main purpose of the advance was to allow the cavalry to raid northward and destroy the Virginia Central Railroad, the only rail link between Lee and Jubal Early's force which had recently raided north almost into Washington, D.C. A secondary purpose was to divert Confederate troops from Petersburg north to Richmond, thus making an attack in conjunction with Burnside's mine more likely to succeed. Accordingly, on the night of July 26th, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock took his II Corps north across James River to threaten the Rebel capital. After a month of relative inactivity this just might catch Lee napping, but no one really expected that. Although his main purpose was to protect the cavalry's flank and rear, Hancock's mere presence north of the James would force Lee to react, and react in strength. He would have little choice but to move troops from Petersburg to the Richmond front. Hancock crossed on a pontoon bridge laid near the top of a loop in the James, also near where a creek (variously known as Four Mile Run, Bailey's Creek, or Deep Bottom Run) flowed south into the river. The mouth of the creek and the hydrology of the loop had created a deep-water area near the mouth of the creek that was well-suited for loading and unloading large vessels, and which had given the area the name of Deep Bottom. (See map.) The Federals maintained two pontoon bridges in this area: the upper bridge, to the west of the mouth of the creek, connecting to Foster's original bridgehead; and the lower bridge, east of the mouth of the creek. Based on a conversation with Foster, whose troops held the bridgeheads north of the James, Hancock elected to cross by the lower bridge. While this would mean he would have to force a crossing of Bailey's Creek in order to threaten Richmond, it would also make it easier to maintain contact with Sheridan's cavalry, which would be operating to his right, and it would give the entire force better access to three roads leading in to Richmond. Going south-to-north, these were the New Market Road, Darbytown Road, and Charles City Road. The Confederates were in the process of constructing an outer line of entrenchments on the west side of Bailey's Creek and along New Market Heights, but Lee did not have enough troops to keep this front well-manned and also have enough men at Petersburg and Bermuda Hundred. Although Federal estimates placed as many as seven Confederate infantry brigades with a total strength of about 5800 men in the area, it appears that Kershaw had only four or five brigades, totalling about 4200 infantry, together with a small force (less than 600 men) of cavalry under Brig. Gen. Martin Gary. Two other brigades, from Wilcox's division, were holding the lines at Chaffin's Bluff. In the best circumstances, Hancock would be able to cross the river, form his troops, and bash in the end of the Rebel lines covering the main roads to Richmond. This would allow the cavalry to range to the north for Hanover Junction, the vital link between Lee and Early. The initial Federal advance on the morning of July 27th, along the New Market Road, was successful, capturing a battery of heavy artillery and a number of prisoners. However, Hancock did not follow up this success quickly, or in force, with the result that the rattled Confederates were able to form a defense line along Bailey's Creek. After weakly probing this position for most of the morning, Hancock declined to storm the position, and then sent Torbert's cavalry division probing northward along the creek. The Federal troopers found that the Confederate position extended farther to the Federal right than had originally been supposed, effectively blocking any advance by the cavalry. Hancock's caution is hard to fathom. He had his entire corps at his disposal, plus two divisions of cavalry, totalling perhaps as much as 24,000 men. One of Grant's staff officers thought Hancock was afraid to press forward because of the stunning flank attack which had fallen upon his troops in the Battle of the Jerusalem Plank Road, one month previous. Regardless of why it happened, a golden opportunity slipped away as Hancock dawdled on July 27th. On the 28th Grant ordered an envelopment of the Confederate left flank in order to free the cavalry for its raid. Accordingly, Hancock shifted troops to the right to support Sheridan's advance on the Darbytown Road, but the Confederates had reinforced the position during the night with Heth's division and planned an attack of their own, to turn the Federal right and drive the Yankees back south of James River. The result was a confused meeting engagement along the Long Bridge Road in which four small Confederate infantry brigades attacked two Federal cavalry divisions. Although the Confederates captured a Federal artillery piece they were driven off in some confusion. Once again a normally aggressive Federal commander failed to press an advantage. Sheridan could have followed up the enemy with his own troops plus Gibbon's division of II Corps, sent to his support, but he instead did nothing. Early in the afternoon Hancock received information that heavy Confederate reinforcements had been sent north of the James and he ceased all thought of offensive action. At 5:00 p.m. Grant and Meade visited Hancock and determined to end active operations on this front. Hancock would stay in place to hold the Confederates in his front. At a cost of about 330 Federal troops, Hancock and Sheridan had drawn all but three of Lee's infantry divisions away from Petersburg. It was time to use the mine.

|

|

||||||||||

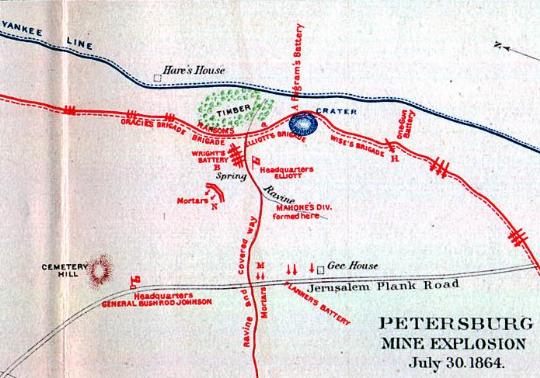

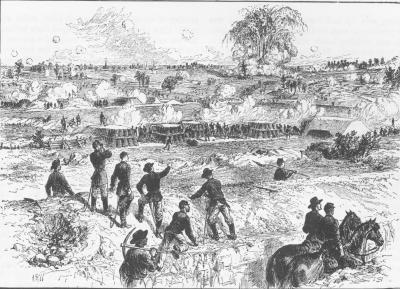

The Crater (July 30, 1864) The key issue in any attack in support of the mine was Cemetery Ridge, a long low elevation about 500 yards in rear of the Confederate line. It was the last piece of high ground between the armies and the city itself. If Federal troops could seize the ridge, Lee's Petersburg position would be in deep trouble. At this point the poor relations between Meade and Burnside enter into the narrative. IX Corps was now part of the Army of the Potomac, and so a former commander of that army (Burnside) was taking orders from someone (Meade) who had once been a subordinate. On July 26 Meade had asked for Burnside's opinion as to how to exploit the mine and the reply -- which was actually rather mild -- had so offended Meade as to provoke an intemperate response. Burnside wanted to have his freshest division lead the attack, sending one regiment from each side to fan out and clear the Rebel works adjacent to the hole blown by the mine, with the rest of IX Corps to follow. Meade wanted nothing to do with diversions and side-shows. He insisted that the lead division move straight forward as rapidly as it could for the ridge beyond the Rebel lines. Although modern Burnside advocates point to this as a serious error on Meade's part, it would pale in comparison to the errors --- mostly by Burnside --- that followed. Burnside wanted the lead division to be 4/IX, under Edward Ferrero, a proven veteran of Antietam and most of the IX Corps campaigns. It was the freshest division, and the largest, in IX Corps. It was also the only collection of black troops in the entire Army of the Potomac. Meade refused to let Burnside use these troops in the lead role, for reasons that are very indicative of the invidious way that politics affected command decisions in the Union army, especially the Army of the Potomac. The Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War, dominated by Radical Republicans, had spent much of the winter of 1863-64 investigating Meade's conduct of the Battle of Gettysburg, with an eye to replacing him in command of the Army of the Potomac. They had failed in this goal, but they had left Meade scarred by the experience. Now, faced with the prospect of sending an entire division of black troops in as the spearhead of an attack in which he had little confidence, Meade did not want to give the Committee an opportunity to say he had willfully sacrificed the black troops in a forlorn hope. As Bruce Catton wrote, it was a sound decision, but also a mistake. When Burnside insisted that Meade consult with Grant on this, the lieutenant general, to his eventual regret, supported Meade. Grant was also unenthusiastic about the prospects for success, having used a couple of mines during his siege at Vicksburg. The mistake was compounded because the final decision was not communicated to Burnside until the day before the attack, and Burnside had made no contingency plans in case his appeal was not granted. For some bizarre reason, he actually resorted to a lottery to decide who would now lead the attack. Of the three remaining divisions, two were led by competant veterans (2/IX, under Robert Potter, and 3/IX, under Orlando Willcox) while the other (1/IX) was led by an incompetant drunk and coward who had sacrificed his men in a foolish attack at the North Anna: James Ledlie. Just to drive home the point, Ledlie's division was composed almost entirely of converted cavalry and heavy artillery units. Ledlie drew the short straw. In addition to this blunder, and despite direct instructions to the contrary, Burnside refused to remove obstructions to artillery fire and movement along his front, for fear that it would tip the enemy off to the coming attack. At 4:45 on the morning of July 30th, the mine was set off, yielding a prodigious explosion and shower of dirt, and the attack went forward. To say that it was a flop would be mammoth understatement. Ledlie's division went forward --- without Ledlie, who remained in the trenches with a bottle of rum --- and immediately occupied the crater made by the explosion, instead of passing around the crater to seize the high ground beyond. Potter and Willcox followed on each flank, but were unable to do more than occupy a few hundred yards of trenches. Rebel reaction was swift, but under-manned: initially the defense consisted entirely of detached artillery positions and a number of Coehorn mortars lobbing shells at the Federals. Although the orders had been to move forward for the ridge beyond the main line, no one was present at the point of attack to get the troops moving and coordinate matters. (One of the problems here was something that is usually overlooked as a difficulty in this entire campaign, i.e., the problems of moving through trench systems under the linear tactics of the day. This had occurred at Spotsylvania and the Petersburg assaults, and would be an issue even during the final breakthrough the following April.) Only the most feeble efforts were made to advance beyond the crater itself, and soon these were hampered by enfilade fire from Confederate batteries to the north and south. (Brig. Gen. E.P. Alexander had suspected a mine in this area, and had positioned several batteries with the object of enfilading a possible breakthrough.) Efforts to suppress this with Federal counter-battery fire were hampered by the presence of a stand of trees between the lines, which Burnside had refused to cut down on the grounds that it might tip off the enemy to the impending attack. A division of troops from the Army of the James attacked on the right and made some headway, and then at 7:30 a.m. Ferrero's men assaulted over the same ground covered by Ledlie. They advanced a little beyond and slightly to the right of the crater but were forced back by fire from the flanks and front. Significantly, their commander, Edward Ferrero --- whose troops had charged across the stone bridge at Antietam --- took refuge in the same trench bombproof with James Ledlie, to share the same bottle of rum. The end result was that some few hundred yards of trenches were occupied and more men were stuffed into the crater, where they could do absolutely no good as combat troops, but were excellent targets for the Confederate Coehorn morters. The few efforts to advance forward --- by scattered detachments of men, not organized brigades --- were broken up by artillery fire and the remnants of Rebel infantry in the area. Confederate reaction was outstanding, for the most part. The regimental officers to either side were able to contain the break once they had recovered from the shock of the explosion. Between 8 and 9 a.m., just after Ferraro's men had fallen back from their attempt to advance beyond the crater, Gen. William Mahone brought his division over to seal the breach. By 9:45, barely 5 hours after the attack had begun, both Grant and Meade were convinced that it was impossible to make further progress, and Burnside was ordered to withdraw his men. For nearly three hours --- until 12:30, when the order finally was sent to the troops --- Burnside argued and prevaricated. He could not believe or accept that his brilliant scheme had come to naught. (He had been so sure of success that his orderlies had been ordered to pack his baggage for the move into Petersburg.) But Mahone had not been inactive and by this time the Federal troops still huddling along the Rebel lines were in no position to retreat. An effort was made to dig a connecting trench to allow them to run back to the Union lines under some protection but a series of attacks by Mahone at about 12:45 and 2:00 finally eliminated the Federal lodgement. Casualties among Ferraro's men were heavy, while prisoners were few. There has been much ink spilled over the failure of this attack both at the time and since. Horace Porter describes an argument between Meade and Burnside that "went far towards confirming one's belief in the wealth and flexibility of the English language as a medium of personal dispute." IX Corps partisans --- and there are some --- argue that Meade's lack of support for the project and interference in Burnside's tactical planning doomed the effort. While there is no denying that Meade and his staff did not provide proper support for the construction of the mine, and there is even a case to be made that Burnside's tactical plan was better than Meade's, the assertion is still nonsense. The attack was doomed the minute that James Ledlie was named to lead it, and that was a decision made by Burnside. It is true that the last minute refusal to allow the black troops to lead the attack forced some change on the IX Corps commander, but he should have let one of his veteran division commanders lead the effort. It is also true that if the original plan had been adhered to --- with regiments sweeping down the Rebel trenches to the left and right --- that the galling enfilade artillery fire which broke up the later efforts to advance would have been suppressed. But the amended plan would have worked just as well if there had been someone on the scene at the point of attack to actually lead the troops and keep them going forward. Apparently Ledlie had not even briefed either of his brigade commanders on what was expected of them! (One of the reasons the attack failed was that the men simply walked up to the crater and then down into it --- after all, rifle pits were a good thing in this war and here was the mother of all rifle pits! But then the steep sides prevented them from getting out. And with Ledlie not present there was no commander for the lead elements.) Burnside spent the entire time at a large Federal battery overlooking the operation. Minor failures included that of V Corps commander Warren, whose front was stripped by Mahone in order to make his counterattack, yet Warren could find no opening for an attack of his own in support of Burnside's effort; and Burnside's refusal to prepare his front for the passage of troops and his refusal to remove obstructions to artillery fire. According to Mahone, there was plenty of time between the explosion and when his troops arrived on the scene; moreover, "after the explosion there was nothing on the Confederate side to prevent the orderly projection of any column through the breach which had been effected, cutting the Confederate army in twain." An energetic commander, with well-led troops, should have been able to get through the gap onto the high ground beyond in that time. But the ultimate and most appropriate comment was that by U.S. Grant: "So fair an opportunity will probably never occur again for carrying fortifications."

|

|

||||||||||

|

Return to Siege main page. Return to list of accounts. Go to previous page. Go to next page. |