Overview About one month after the expedition that resulted in the capture of Fort Harrison and the extension to the Peebles Farm position on the Southside, Grant determined to once again strike at each end of the Rebel line. This time, instead of first unleashing his right hand and then launching his left as a response to the Rebel reaction, Grant would launch both hands simultaneously. On the Richmond front the objective would be to cave in the northern flank of the new Rebel lines in front of the city. On the Southside the objective would be once again to block the Boydton Plank Road and the Southside Railroad. The operation in front of Richmond would be commanded by Maj. Gen. Godfrey Weitzel, who had succeeded E.O.C. Ord in command of XVIII Corps after the Fort Harrison fight. |

|

||||||||||||

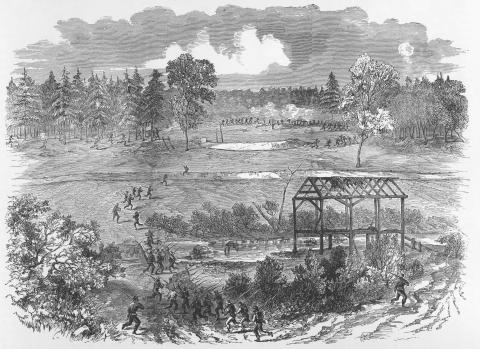

First Hatcher's Run Once again the geography and geometry of the lines southwest of Petersburg dictated the course of the action there. After the encounter at Peebles Farm, Lee had continued work on his Boydton Plank Road line, extending it southwest from Petersburg as far as Hatcher's Run, a significant stream running roughly northwest to southeast. The Confederates then refused their right flank behind Hatcher's Run as far as a large mill pond. Since this extension actually gave Lee ready access to the Federal rear areas around Peebles Farm and Globe Tavern, the Yankees were forced to construct a fairly substantial reverse line to protect their rear. Prompted by reports that this new Rebel line was incomplete and thinnly held, Grant wanted to try three things at once on the Southside. First, Gregg's cavalry division would strike south and then west and north to reach the Boydton Plank Road. Since this was known to be the main avenue by which wagon trains brought supplies into Petersburg from Stony Creek Station on the Weldon Road, it was thought such a presence would disrupt and destroy the movement of large amounts of Confederate supplies. With winter coming on this might prove significant. Secondly, IX Corps under Parke, and V Corps under Warren, were to press up close to the Boydton Plank Road line and see if it was strongly held. If the works were weakly manned, Grant wanted a prompt and vigorous attack, but if they were held in strength Parke and Warren were not to attack, but simply to demonstrate. Finally, the main blow would be delivered by "Hancock's Foot Cavalry," as the II Corps had taken to calling themselves. Hancock would take his troops southwest behind the Federal lines fronting the Boydton Road position, cross Hatcher's Run and then turn nearly due west along the Dabney's Mill Road. Once he reached the Boydton Plank Road, Hancock would be in position to do either of two things: (1) He could proceed further west along the White Oak Road, deep into the Confederate rear, with his objective being to reach the Southside Railroad and perhaps complete the investment of the city; or, (2) He could strike north along the Boydton Plank Road to where it crossed Hatcher's Run near Burgess Mill and attempt to turn the flank of the Boydton line north of the stream. Of the 57,000 bluecoats in the Petersburg lines, fully 43,000 were detailed for the mobile force in this operation. At 3:00 a.m. on the morning of October 27th, Parke moved out westwards toward the Boydton Plank Road line. Although he had only a short distance to go he made slow progress and it wasn't until as late as 9:00 a.m. that he had determined that the enemy position was not unfinished, nor poorly manned, as had been thought. Warren, also moving slowly, made a similar report at about the same time. Since the plan did not envision a direct attack upon strongly held works, Meade ordered Parke to entrench and make connection with the existing Federal works, while Warren was to lend support (Crawford's division) to Hancock's column. It quickly developed that the operation was not going to succeed. Warren had a devil of a time extending Crawford towards Hancock, as the terrain provided more of an obstacle than did the Rebels, and the link-up was in fact never made, leaving II Corps with its right flank in the air. Meanwhile, after a long and circuitous march, II Corps arrived at the Boydton Plank Road crossing of Hatcher's Run. It was now about 1:00 p.m., and the Federals were discovering -- aided in part by a personal reconnoissance by U.S. Grant -- that the enemy held the north side of Hatcher's Run in some force. The Federal plan had depended on getting behind the Rebel flank before they could oppose the crossing of the run, and this had not been accomplished. A slow start, poor weather, and horrendous terrain had all contributed to the delays. Still, Hancock made ready to attack across the run late in the afternoon. The Confederates, however, had not been idle. Hancock was in an exposed position. To his front was the force defending across Hatcher's Run, composed of Heth's and Mahone's veteran divisions. Behind him was Gravelly Run, with the crossing now blocked by W.H.F. Lee's cavalry. Only to his right, along the Dabney's Mill Road, could he move his men. And A.P. Hill was making plans to attack the Federals from front, flank, and rear. If the Rebels attacked and II Corps collapsed as it had at Reams Station two months earlier, it could well be destroyed. The Confederate attack came at about 4:00 p.m., with Heth and Mahone pressing forward across Hatcher's Run, Hampton attacking on the left flank, and W.H.F. Lee attacking across Gravelly Run in the rear. But the Federal perimeter held, although Mahone had a brief initial success against Hancock's exposed right flank, and the Confederates were driven off by nightfall. Brig. Gen. Thomas W. Egan, commanding Gibbon's division (2/II) in the absence of that officer, particularly distinguished himself. Despite this tactical success, Hancock was in a tight spot and he knew it. Gregg's cavalry had used up their ammunition, and the only connection with the rest of the army was a single narrow road. The decision to withdraw was made, with the first troops beginning to move at 10:00 a.m. and the last pulling out at around 1:00 a.m. Because of a shortage of ambulances, some wounded had to be left behind. Federal casualties in this operation were listed as 1,758, mostly from II Corps. Confederate casualties are not listed, but are assumed to be light, although Hancock reported taking about 700 prisoners and Warren another 200. Wade Hampton's two sons were both wounded, one mortally, in the Confederate attack. This operation was the last service with the Army of the Potomac for the legendary Winfield Scott Hancock. On November 26 he requested a leave to allow his still troublesome Gettysburg wound to heal. Later he would be assigned to Sheridan's former command in the Shenandoah. Hancock had been one of the stalwarts of the Army since the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, but his Gettysburg wound still gave him trouble and the poor performance of his troops in recent months had led to some serious dissension and squabbles between him and the division officers under his command. His place was ably taken by Meade's chief of staff, A.A. Humphreys.

|

|

||||||||||||

Williamsburg Road North of the James Butler sent Weitzel and Terry into action about two hours after the time Warren and Parke began their movements on the Southside. Terry was to advance up the Darbytown and Charles City Roads and demonstrate against the Rebel works blocking those avenues of approach. Meanwhile, Weitzel's column would pass behind Terry all the way north to the Williamsburg Road and the old Seven Pines battlefield, and advance towards Richmond. If Terry was successful in occupying the Rebel defenders on the Northside, then Weitzel should face only token opposition and be able to take the Rebel lines in flank. The plan was sound and was initially successful. However, the Confederate defenses at Richmond were now commanded by Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, who had just recently returned to duty. Longstreet correctly recognized Terry's prolonged skirmish activity as a feint, and was therefore able to shift troops to block Weitzel's column rather easily. The Federals reached the Williamsburg Road at about 1:00 p.m., and encountered the Rebel works an hour later. Although he recognized that the enemy lines were thinnly held, Weitzel diddled about for over two hours, probing the lines and sending brigades hither and yon. Finally, at 3:30 Weitzel sent forward his attack, consisting of nothing more than two of his seven brigades. In the interim, of course, the thin Rebel defense line had been bolstered by two veteran infantry brigades, Bratton's South Carolinians and the remnant of the Texas Brigade. So poorly was Weitzel's attack made that both Confederate brigades charged out of their works after stopping the initial Federal thrust, and were thereby able to sweep up a significant haul of prisoners. This ended Weitzel's "effort" to take Richmond. The entire affair cost the Army of the James 1,600 casualties, many of them being men captured in the repulse of Weitzel's attack. Rebel losses were reported as being only 64; while that figure may be too low, the disparity nonetheless reflects the ease with which this prong of the attack was stopped. |

|

||||||||||||

|

Return to Siege main page. Return to list of accounts. Go to previous page. Go to next page. |